Tumor

cells gain access to the leptomeninges by hematogenous dissemination or by direct

extension. Once these cells reach the CSF, they are disseminated throughout the neuraxis

by the constant flow of CSF. The CSF travels from the ventricles through the foramen of

Magendie and Luschka to the spinal canal and over the cortical convexities to the

arachnoid granulations. Infiltration of the leptomeninges by any malignancy is a serious

complication that results in substantial morbidity and mortality.

Neoplastic meningitis occurs in approximately 5% of

patients with cancer. This disorder is being diagnosed with increasing frequency as

patients live longer and as neuroimaging studies improve. The most common cancers to

involve the leptomeninges are breast cancer, lung cancer, and melanoma. Without

treatment, the median survival of patients diagnosed with this disorder is 4 to 6 weeks,

with death resulting from progressive neurologic dysfunction.

The goals of treatment in patients with leptomeningeal

metastases are to improve or stabilize the neurologic status of the patient and to prolong

survival. Standard therapy involves RT to

symptomatic sites of the neuraxis and to disease visible on neuroimaging studies, in

addition to intrathecal chemotherapy. These therapies increase the median survival to 3 to

6 months and often provide effective local control, allowing patients to die from

systemic rather than neurologic complications of their neoplasm. Early diagnosis and

therapy are critical to preserving neurologic function.

Patient Evaluation

Patients present with signs and symptoms ranging from

injury to nerves that traverse the subarachnoid space, direct tumor invasion of the brain

or spinal cord, alteration in the local blood supply, obstruction of normal CSF flow

pathways leading to increased intracranial pressure, or interference with normal brain

function. Patients should have a physical examination with a careful neurologic

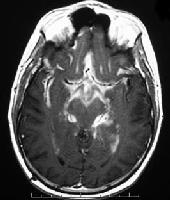

evaluation; MRI of the brain and spine should also be done, if the patient has appropriate

neurologic symptoms or signs. A definitive diagnosis is most commonly made by lumbar

puncture. The CSF protein is typically increased, and there may be a pleocytosis or

decreased glucose levels. The CSF cytology is positive approximately 50% of the time

with the first lumbar puncture, and 85% of the time after three CSF examinations in

patients who are ultimately proven to have neoplastic meningitis. However, the CSF

cytology is persistently negative in 10% to 15% of patients with leptomeningeal

carcinomatosis. In these cases, (1) a suspicious CSF examination (eg, increased protein,

low glucose, and/or a pleocytosis) combined with suggestive clinical findings (eg,

multifocal neuraxis involvement, such as cranial nerve palsies and a lumbar radiculopathy

that cannot be explained otherwise); and/or (2) suggestive radiologic features (eg,

subarachnoid masses, diffuse contrast enhancement of the meninges, or hydrocephalus

without a mass lesion) can be sufficient to treat when the patient is known to have a

systemic malignancy. Although a positive CSF cytology in patients with solid tumors is

virtually always diagnostic, reactive lymphocytes from infections (eg, herpes zoster

infection) can often be mistaken for malignant lymphocytes.

Patient Stratification for Treatment

Once the diagnosis has been

established, the patient's overall status should be carefully assessed to determine how

aggressively the carcinomatous or lymphomatous meningitis should be treated.

Unfortunately, this disease is most common in patients with advanced, treatment-refractory

systemic malignancies for whom treatment options are limited. In general, fixed neurologic

deficits (such as cranial nerve palsies or paraplegia) do not resolve with therapy,

although encephalopathies may improve dramatically. As a result, patients should be

stratified into “poor risk” and “good risk” groups.

The poor-risk group includes patients with a low KPS; multiple, serious, fixed neurologic

deficits; extensive systemic disease with few treatment options; bulky CNS disease; and

neoplastic meningitis related to encephalopathy. The good-risk group includes patients

with a high KPS, no fixed neurologic deficits, minimal systemic disease, and reasonable

systemic treatment options. Many patients fall in between these two groups, and clinical

judgment will dictate how aggressive their treatment should be.

Treatment Algorithm for Neoplastic Meningitis

Patients in the poor-risk group are usually offered

supportive care measures. RT is commonly administered to symptomatic sites (eg, to the

whole brain for increased intracranial pressure or to the lumbosacral spine for a

developing cauda equina syndrome). If the patient stabilizes or improves, a more

aggressive treatment approach may be considered. Patients with exceptionally

chemosensitive tumors (eg, small cell lung cancer, lymphoma) may be treated.

Good-risk patients can receive radiation to symptomatic

sites and to areas of bulky disease identified on neuroimaging studies. In addition,

intrathecal or intraventricular (using a surgically implanted subcutaneous reservoir and

ventricular catheter [SRVC]) chemotherapy can be administered; systemic chemotherapy can

be considered. Initially, intrathecal chemotherapy is usually given by lumbar puncture,

and the SRVC is placed later to administer the drugs more conveniently. Initiation of

chemotherapy should not be delayed for flow study. When dosing intrathecal chemotherapy

for adults, no adjustment is made based on weight or body surface area. With methotrexate,

thiotepa, and cytarabine, a typical dosing schedule is initially twice a week for 4 weeks;

if the CSF cytology becomes negative, then continue with once-a-week administration of

intrathecal chemotherapy for another 4 weeks, followed by once-a-month maintenance doses.

Methotrexate (10-12 mg) is the drug most frequently used for intrathecal administration.

Oral leucovorin (folinic acid) can be given (10 mg twice a day for 3 days starting the day

of treatment) to reduce possible systemic toxicity without interfering with the efficacy

of methotrexate in the CSF. Intrathecal thiotepa (10 mg) can also be used in solid tumors,

and cytarabine (50 mg) is often administered for lymphomatous meningitis. A depot form of

cytarabine is now available that allows patients with lymphomatous meningitis to be

treated every 2 weeks initially (rather than twice per week) followed by once-a-month

maintenance treatment. In a randomized controlled trial, depot cytarabine was found to

increase the time to neurologic progression, with a response rate comparable to

methotrexate, while offering the benefit of a less demanding schedule of injection. One

study suggests that high-dose systemic methotrexate might be better than intrathecal

therapy. If an SRVC is placed, a CSF flow scan should be strongly considered. CSF flow

abnormalities are common in patients with neoplastic

meningitis and often lead to increased intracranial pressure. Administering chemotherapy

into the ventricle of a patient with a ventricular outlet obstruction increases the

patient's risk for leukoencephalopathy. In addition, the agent administered will not reach

the lumbar subarachnoid space where the original CSF cytology was positive. CSF flow scans

are easily performed in most nuclear medicine departments. Indium 111-DTPA is administered

into the SRVC, and imaging of the brain and spine is performed immediately after injection

and then imaging is done again at 4 and 24 hours. If significant flow abnormalities are

seen, RT is administered to the sites of obstruction and a CSF flow scan is repeated. If

CSF flow normalizes, which occurs most commonly in radiosensitive neoplasms, intrathecal

chemotherapy commences. If significant flow abnormalities remain, then the patient should

be treated as a poor-risk patient (ie, with supportive measures). For patients with a

normal CSF flow scan and otherwise stable disease, induction intrathecal chemotherapy

should be given for 4 to 6 weeks (see ) and then the patient should be reassessed

clinically and with a repeat CSF cytology. Because the cytology is much less likely to be

positive from the SRVC than from the lumbar subarachnoid space, it is critical that it be

sampled from the site where the cytology was originally positive. If the CSF cytology was

originally negative, then reassess from the lumbar region. If the patient is clinically

stable or improving and there is no clinical or radiologic evidence of progressive

leptomeningeal disease, the patient should receive another month of “induction”

intrathecal chemotherapy or should consider switching intrathecal drugs for 4 weeks. This

regimen should be followed by 1 week per month of maintenance therapy if the cytology has

converted to negative. The CSF cytology status should be followed every month.

Progressive Disease

The patient's clinical and CSF

status should be followed every 2 months. However, if the patient's clinical status is

deteriorating from progressive leptomeningeal disease or if the cytology is persistently

positive, the clinician has two options: (1) chemotherapy; (2) supportive care, which may

include RT to symptom sites. |