| This does not mean that postmenopausal hormone therapy should never

be used. Postmenopausal symptoms — such as hot flashes and vaginal dryness

or discomfort — remain a valid indication in the absence of

contraindications such as a history of venous thromboembolism or coronary

disease. For symptoms of genital atrophy alone, local estrogen or nonhormonal

lubricants may be sufficient and should be considered. Although there are other

possible treatments for vasomotor symptoms — for example, selective

serotonin-reuptake inhibitors — hormone therapy is very effective and

still reasonable as first-line treatment. Because vasomotor symptoms are

generally transient, short-term use (for no more than two to three years) is

all that is generally needed, and such use carries few risks. Using the minimal

dose of estrogen that controls symptoms (e.g., 0.3 mg rather than 0.625

mg of conjugated estrogen) makes sense, although there are no long-term data

indicating that a lower dose reduces risk.

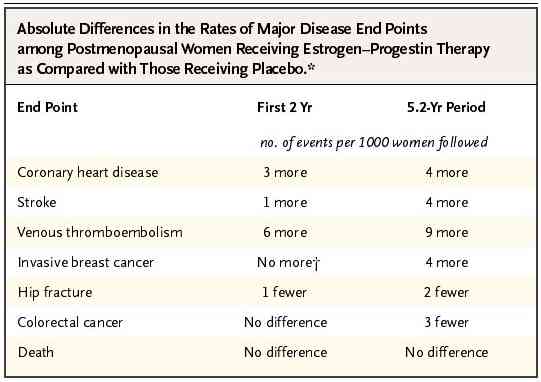

What about women who are using postmenopausal estrogen–progestin therapy

for reasons other than control of symptoms? On the basis of available data,

these women should be advised to stop. Long-term use cannot routinely be

encouraged for the protection of bone, given the availability of alternative

therapies, and there are no data from large clinical trials to support the

belief that long-term therapy will help women preserve cognitive function or

maintain a youthful appearance.

That said, there is no urgency to stop hormone therapy abruptly. In women

whose symptoms recur after stopping, therapy can be gradually tapered (by

reducing the frequency of administration, the dose, or both) over a period of

weeks to months. For a small number of women — those with persistent

symptoms and reduced quality of life — continued treatment may be

justified, as long as they understand the potential risks and the alternatives.

The findings of the WHI and other trials do not rule out the possibility

that some postmenopausal women might derive cardiovascular benefit from hormone

therapy. Nonetheless, our current ability to identify "good

candidates" for hormone therapy is too rudimentary to support differential

prescribing. Thus, the prudent approach is to avoid hormone therapy for the

purpose of long-term prevention of disease.

The WHI findings have led some younger women who use oral contraceptives or

who use hormone therapy after premature menopause to wonder whether they should

stop. Studies of hormone therapy in women 50 years of age or older, however,

cannot be generalized to these groups.

In response to the WHI, other hormonal regimens or preparations have been

touted as alternatives to conjugated estrogen with medroxyprogesterone.

Estrogen therapy alone (without a progestin) is not recommended unless a woman

has had a hysterectomy, because it is associated with increased risks of

endometrial hyperplasia and cancer. More information about the long-term

effects of estrogen alone after hysterectomy should be forthcoming from an

ongoing part of the WHI study. Different formulations (including "natural"

estrogens or progesterone) or transdermal administration has also been

suggested. However, their long-term effects have simply not been studied. On

the basis of available data, the Food and Drug Administration recently

recommended that labeling for all postmenopausal estrogen and

estrogen–progestin products include a boxed warning emphasizing the

associated risks of coronary disease, stroke, and breast cancer.

What should postmenopausal women do now? Women older than 65 years of age or

younger women with other risk factors for osteoporosis should have their bone

mineral density measured. Women should routinely be advised to consume adequate

calcium and vitamin D and to engage in weight-bearing exercise. For women who

have osteoporosis, the bisphosphonates alendronate and risedronate substantially

reduce the risk of both hip and vertebral fractures. The selective

estrogen-receptor modulator raloxifene also reduces the risk of vertebral

fracture, although it has not been shown to reduce the risk of hip fracture. In

contrast to estrogen, it appears to reduce the risk of invasive breast cancer

but does not improve (and may cause) menopausal symptoms. Raloxifene also

increases the risk of venous thromboembolism, although its effects on

cardiovascular disease remain uncertain.

To reduce cardiovascular risk, coronary risk factors should be assessed,

including reevaluation of the lipid profile, which may worsen after the

cessation of hormone therapy. A healthful diet, exercise, and smoking cessation

should be encouraged; medications including statins and antihypertensive agents

should be used in appropriate patients. The combination of these approaches

is much more likely than estrogen–progestin therapy to optimize

health and longevity in postmenopausal women. |